Cornell is leading a project to deploy seismometers along the Alaskan Peninsula.

Geologists to deploy seismometers along Alaskan Peninsula

By Syl Kacapyr

Using a fleet of airplanes, ships and intrepid scientists, Cornell is leading the largest single deployment of seismometers along the Alaskan Peninsula – a $4.5 million endeavor that geologists from across the country hope will solve long-standing mysteries about the region and the planet.

The seismometers are scheduled to be deployed in spring 2018, with the goal of beginning data recovery efforts in summer 2019.

“This is something I’ve wanted to see done for a long, long time,” said Geoff Abers, professor of earth and atmospheric sciences and lead investigator for the Alaska Amphibious Community Seismic Experiment. The effort is funded by the National Science Foundation and includes eight research institutions. “I’ve been working off the Alaskan Peninsula since 1990, and it became obvious that the only way to get something of this scale to work is in this kind of collaborative mode,” he said.

Scientists have been attracted to the region because of the subduction zone located at the bottom of the ocean where the Pacific and North American tectonic plates collide. Ninety percent of all U.S. earthquakes occur here, and it is the only location in North America where magnitude 8 and 9 earthquakes have been recorded. Most of the continent’s known volcanic eruptions have occurred along this subduction zone as well. Despite being such a geologically active area, the remote region hasn’t been monitored very well, especially at the ocean bottom, according to Abers. But recent improvements to seismometer technology and reliability are providing an opportunity to do so.

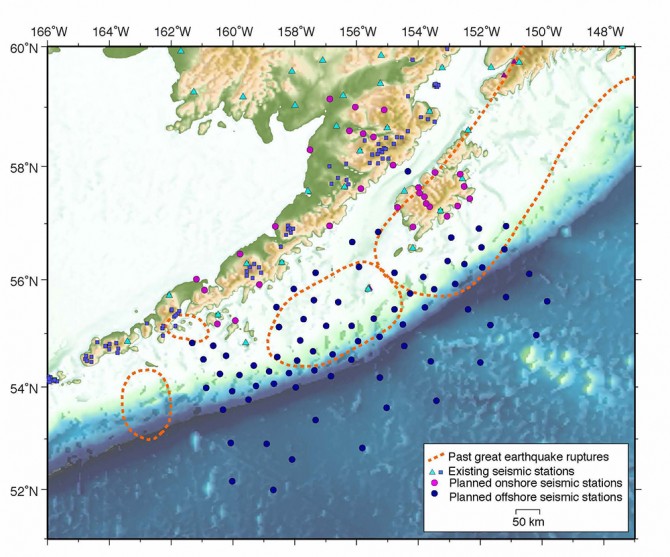

The seismic experiment will scatter 105 high-end seismometers off a 435-mile-long stretch of the peninsula’s coast that includes the communities of Kodiak, King Salmon and Sand Point. Broadband seismic equipment will be buried on various islands and ocean-bottom seismometers deployed as far off shore as 300 miles. The array will cross the Aleutian Trench where the tectonic plates converge.

“We’ll be using signals from earthquakes we record to try and learn more about what the stuff down there is made out of,” said Abers. “Where do the magmas that show up in volcanoes come from? Somewhere below the crust they form, and there’s a lot of debate about what that process is. And how does that actually trigger the volcanos and why are they where they are?”

Another mystery geologists will examine is why one particular stretch of the subduction zone hasn’t recorded a major earthquake in the last several decades while every other stretch has. “Is there something different about the character of the sea floor here that might help us understand why. Is it a much smoother sea floor or do the faults go deeper?” asked Abers.

Abers worked with his colleagues to map the best drop location for each seismometer and is currently coordinating a deployment schedule with a fleet of research ships. He also worked with Alaskan landowners, educators and pilots to negotiate land-based locations. Once data is collected it will be provided to the entire scientific community. “There’s a lot of excitement and anticipation for the data,” said Abers.

Other institutions involved with the project are Colgate University, the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Washington, the University of California-Santa Cruz, the University of Colorado, Columbia University, Washington University in St. Louis, and the University of New Mexico. Ocean-bottom seismometers are provided by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Syl Kacapyr is public relations and content manager for the College of Engineering.

Media Contact

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe